Video selection

Good afternoon, my name is Simona Levi. I am the coordinator of Xnet, the Institute for Democratic Digitalisation, an organisation that has been working since 2008 to defend digital rights and to update democracy in the digital age.

Xnet is also known for its successful conviction in Spain of 65 bankers and politicians, including the former Minister of Economy and Director of the International Monetary Fund, because of the 2008 crisis.

So, we work to preserve the internet as a democratic tool and to improve institutions for a better democracy.

Digital transformation is currently at the centre of the European agenda.

Based on our concrete experience on the field and on a case study in education that I’ll expose later on, we have identified significant gaps in the foundations on which European societies are being digitalised.

These observations were shared with the late president of the European Parliament, David Sassoli, who, via the European Parliament Research Service, commissioned us a report as a policy instrument to promote a more democratic digitalisation.

This resulted in our 188-pages reflection paper titled “Proposal for a Sovereign and Democratic Digitalisation of Europe,” available at the Publication Office of the European Union.

We start from a definition.

What do we mean by “democratic and sovereign digitalisation”?

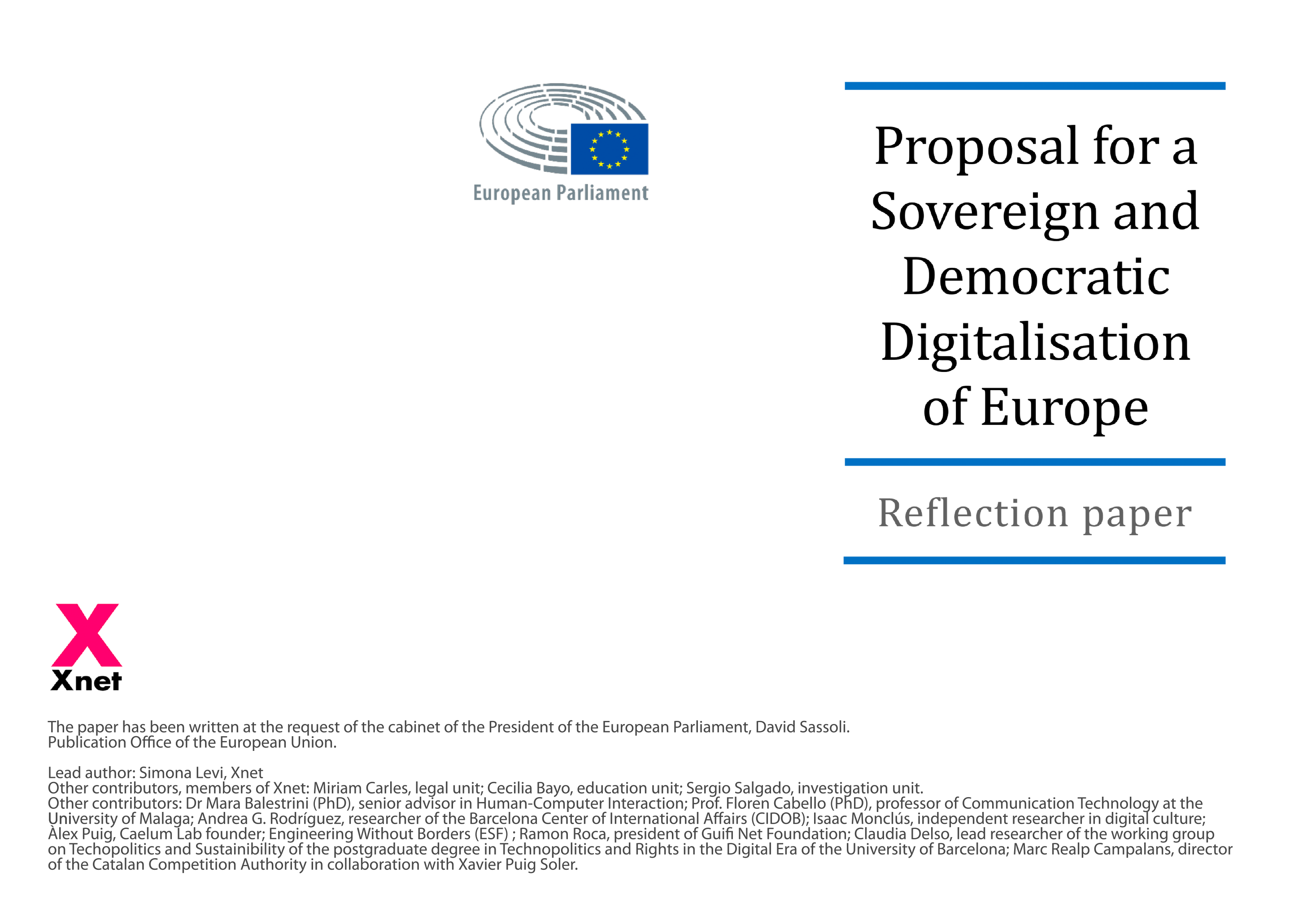

Democratic Digitalisation refers to a digital transition based on human rights, by design and by default.

Sovereign Digitalisation refers to a digitalisation in which even the smallest actor in the democratic architecture – that means, each citizen, all the citizens – can control, in a disintermediated way, the use and destination of the content they create and the data they generate.

As I said, although digitalisation is now a priority on the EU political agenda, the digitalisation of societies has been underway for half a century. The question, obviously, is not whether digitalisation will happen or not, but whether it is democratic and, therefore, beneficial to the majority, or not.

The narrative around digitalisation often focuses on futuristic projects.

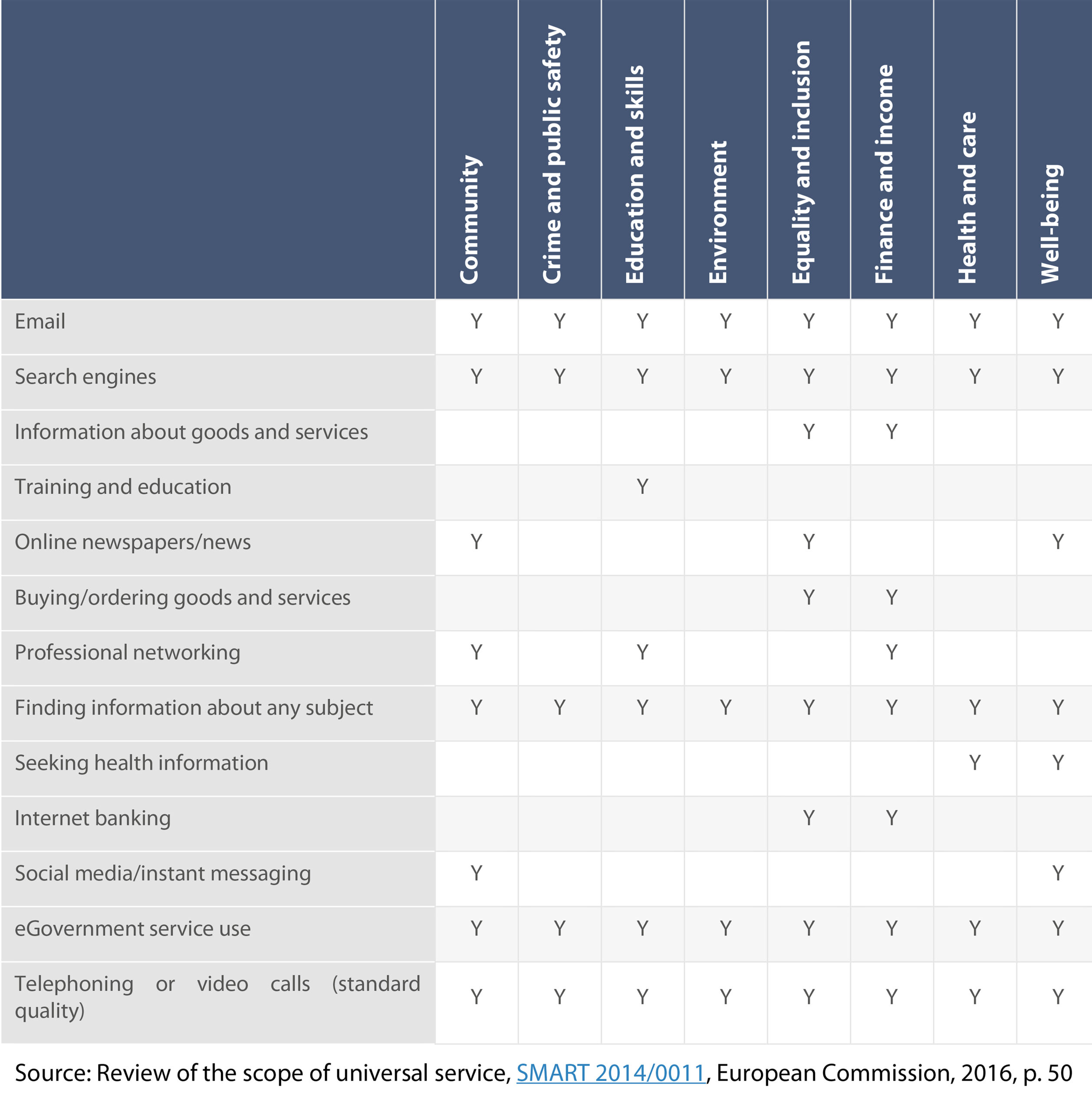

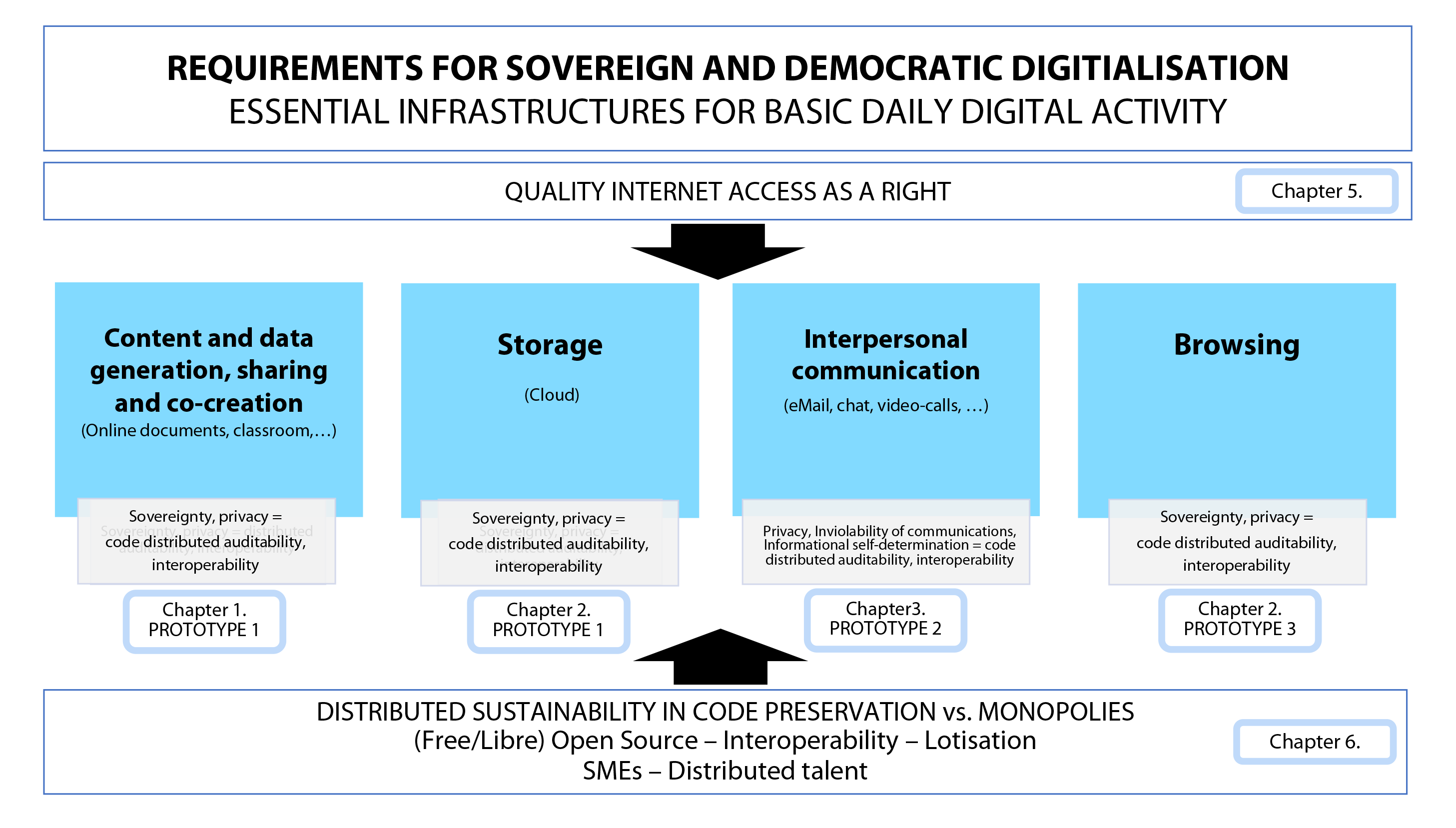

However, there is a forgotten and unavoidable layer before all this. The one that enables daily digital life in all activities of society, from essential services to individual use. I mean:

content creation and storage; online interpersonal communication; browsing and even Internet access

This layer is often taken for granted by our institutions, when in fact it needs serious analysis to ensure that Europe’s digital future is not being built on toxic foundations for the safeguard of human rights.

When the basic layer of daily digital life systematically violates the rights of its users, everything that is done with it will happen in a framework without democratic guarantees.

We believe that this responsibility falls on our institutions. The success of digitalisation must not come with the destruction of fundamental rights as a collateral damage.

In order to guarantee compliance with democratic principles, the digital daily tools must permit

a) As said, that the users remain in control of data and content, and, to guarantee a), b) the possibility to audit the tools to know what they are executing; this means that their source code must be accessible, available to be audited in a distributed and disintermediated manner by anyone.

From this perspective, only free software tools meet these requirements.

Free software (FLOSS) has also another fundamental advantage: it promotes entrepreneurship as it is available to both the public and private sectors, maximising the value of public investment.

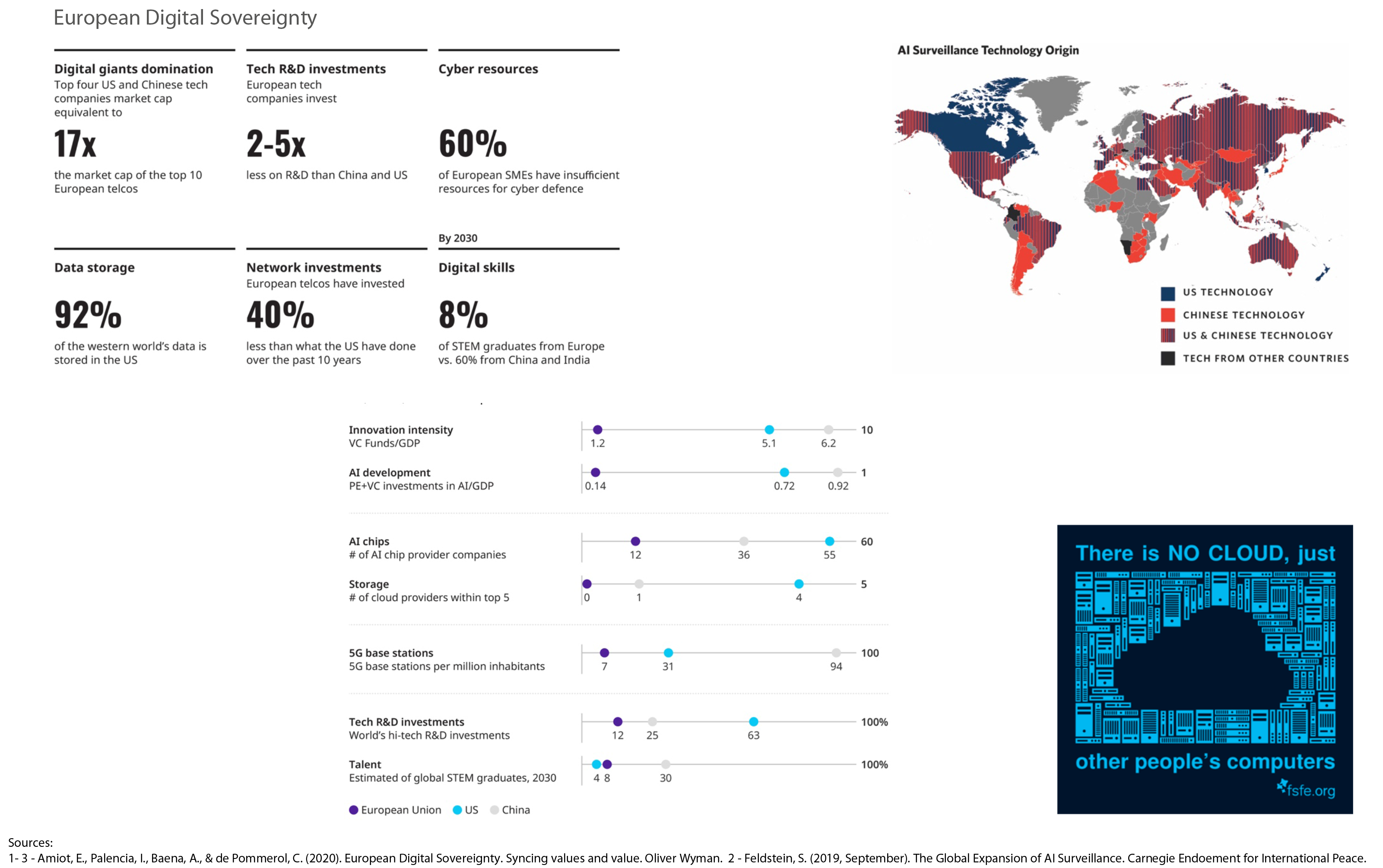

On the contrary, the dominance of a few Big Tech companies in providing the basic digital layer, even in institutions and essential services, sends a very wrong signal to the market: that digitalization can occur at the expense of small and medium-sized enterprises, of innovation, and, often, of human rights too.

Lately the EU wants to change this course; but this could be done faster and deeper.

Our report and our way of working are based on praxis. The report proposes 3 prototypes for democratic digitalisation. It also suggests to refocus digital entrepreneurship by making respect for human rights the raw material of a distributed business model for the digital transformation of Europe.

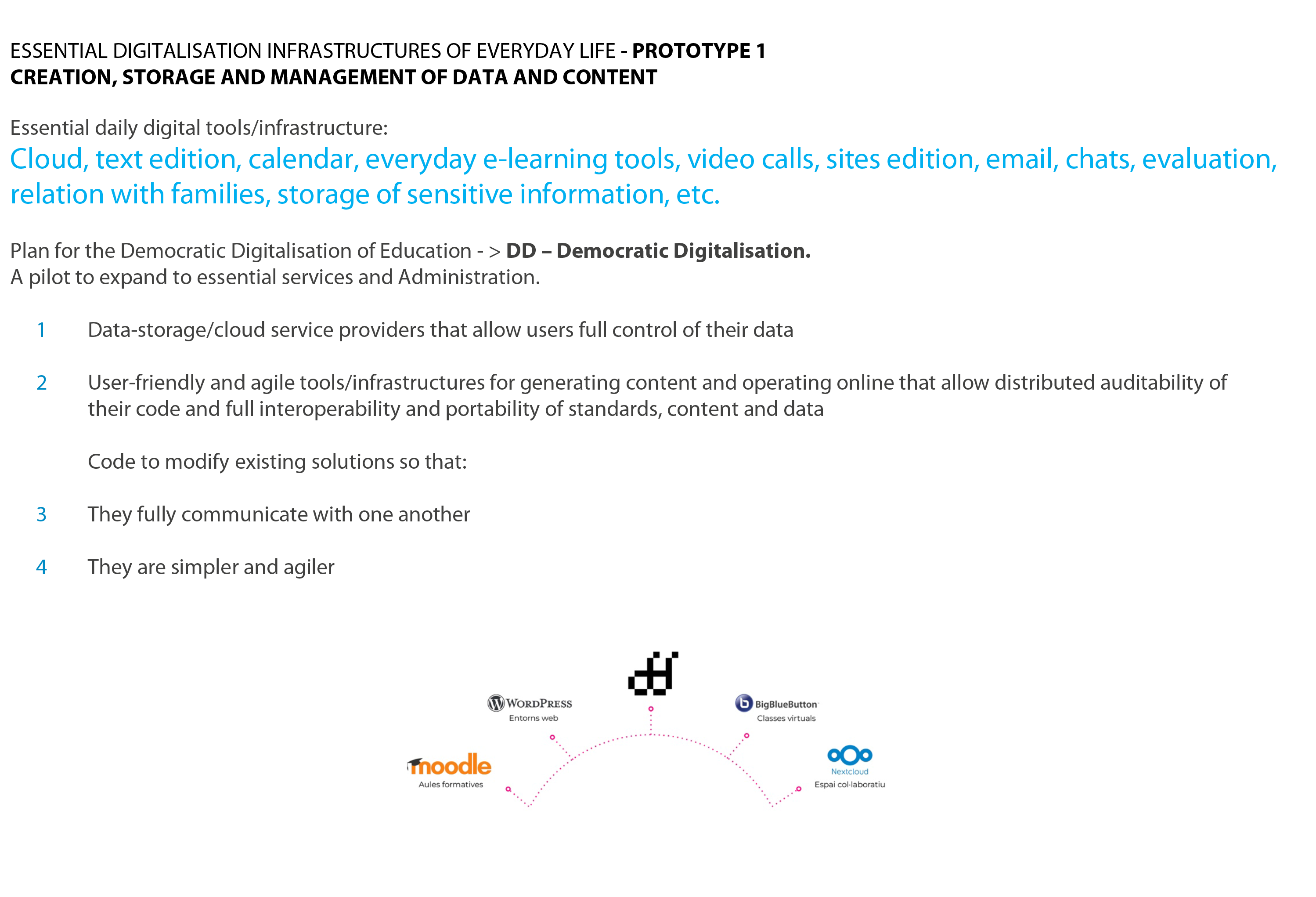

The first prototype we propose is based, as mentioned, on our field experience.

In 2019, several families in Barcelona were opposing that the digitalisation of the education of their children, even those of a very young age – from the age of 4 -, was carried out solely through instruments in which the data and content were managed by Big Tech and with no other solid options available. For this reason, we designed the Plan for the Democratic Digitalisation of Education, which included a substitute digital tool, called “DD”, for Digital Democratic.

As hackers say, “we should never solve a problem twice”. We didn’t invent the wheel: the necessary tools to create alternatives already exist.

DD is the complete merging of existing and widely established free auditable software.

This is not new. What is new is to make them work as if they were one. This is where we innovate; by proposing an institutional commitment to improve them, make them more user-friendly and flashier, so that they can communicate with each other completely, in short, equip them to compete with the big tech tools. It is not only possible but also cost-effective, and, we believe, it is an institutional duty.

The DD tool is needed. We state this with confidence as we are currently in negotiations with institutions and civil society in several countries where Data Protection Authorities have already criticised the use of Big Tech in education. These countries include two Länder in Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, and France, so far. (France is not because of DP…)

Everyone acknowledge that there is no alternative yet, and the lobbying pressure is immense, as my colleagues will explain further on. This is why forming alliances between countries is also challenging.

And this is why we need Europe to take action on the matter.

Between 80 and 92% of European data and content are generated and stored in non-European Big Tech tools.

The DD is not a product. I am an activist, not a service provider, I’m not here to sell anything. The DD aims to be the embryo of a free and public European code that is auditable, easily usable, interoperable and sovereign. A European public code for education and then for all other essential services. The code should be guarded by the EU and governed by the principles of the purpose economy. It should be open so that any government or private willing to contribute can be its co-creator. It should be free software so that every country, institution, school, service or individual can use it and adapt it to their needs, and so that any tech company should be able to provide it as a service, breaking the current macro-monopoly and finally enabling the existence of a robust technological entrepreneurial ecosystem at various scales in Europe.

We believe this is the practical basis for a sovereign and democratic digitalisation of the EU.

We presented the plan to the institutions. The Barcelona City Council agreed to generate a very small tender so that some companies could develop the proposed code.

It is currently implemented as a pilot in 11 schools in Barcelona and we are initiating collaborations with Catalonia and the Bolzano region in Italy, plus negotiating with the aforementioned regions.

Despite receiving significant interest from schools, teachers, families and the sector, both in our region and elsewhere, the conditions are very difficult. Particularly, the project is underfunded, preventing it from scaling as much as the demand requires; not enough so that other regions can try it so to decide if they want to sum in the project as co-developers. An EU legitimacy and coalition is needed, so that local institutions willing to make the change don’t feel that they might be left alone.

In summary, our goal is to guarantee, with your help, an intranational European consortium around this code to generate the European public code for essential services.

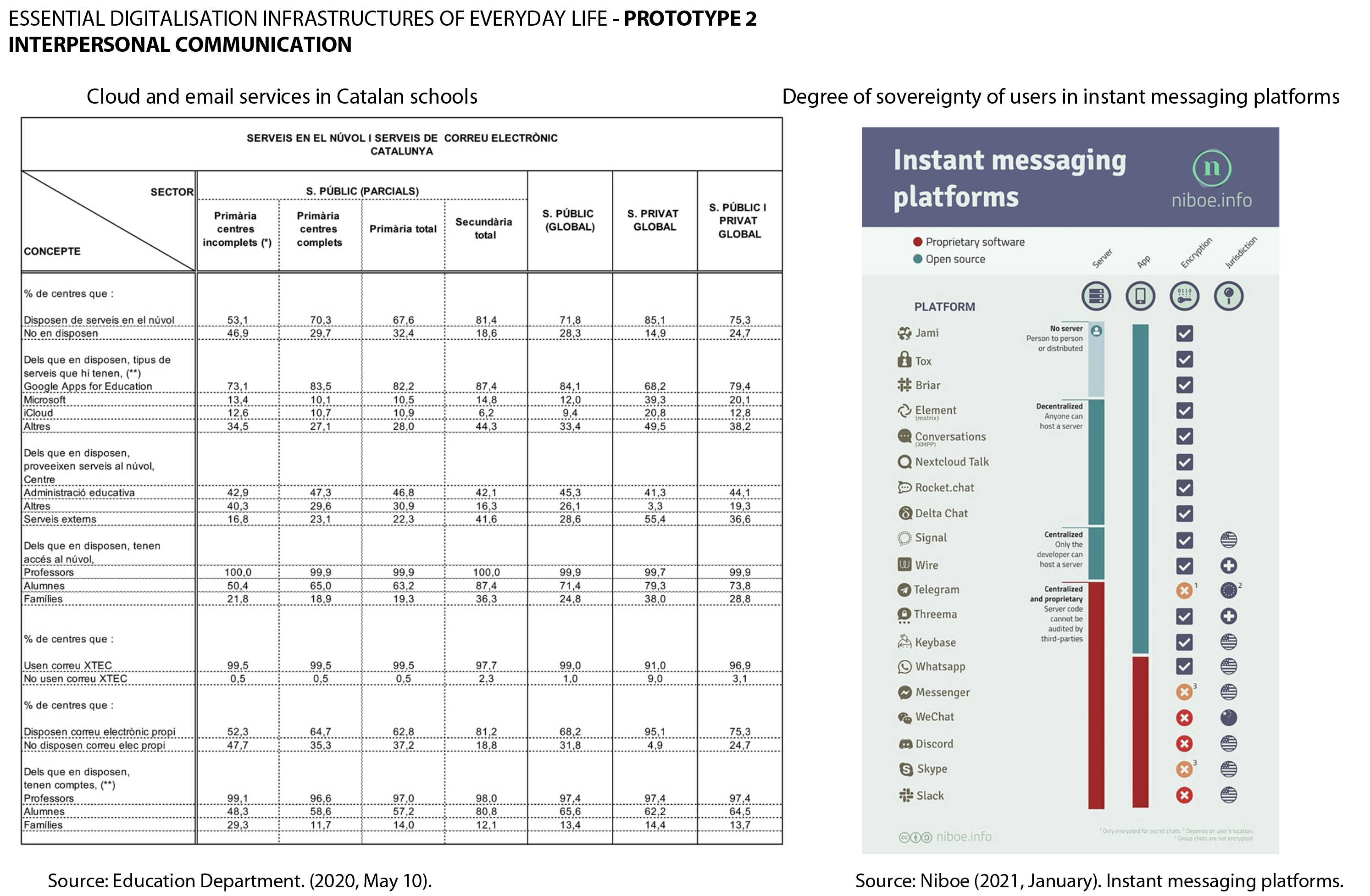

2- The second prototype proposed in our report addresses the same needs. It refers to the interpersonal communication system, particularly what is commonly known as “email.”

It is estimated that 3.9 billion individuals use email services. According to Google, approximately 1.5 billion use Gmail (the email service they provide since 2004).

Additionally, around 400 millions users have Microsoft email accounts.

The aforementioned actors are dominant players in the email market that they have penetrated by offering an email service free of charges, despite the fact that it is a service with high costs.

The free provision of these services by for-profit companies it is problematic in a market that claims to be competitive and democratic. The result is a dominant-player situation, a de facto private monopoly, in an essential infrastructure such as interpersonal communication.

Furthermore, these services are currently designed as centralised services, which raises several issues related to sovereignty and privacy, particularly about the right to the secrecy of communication—a right that we conquest in the 18th century.

In this context, it is important to analyse to what extent the right to the inviolability of communications, which is essential for democratic societies, can be left exposed by our institutions to profit interests in an imbalanced market.

This is why we suggest a sovereign solution for ’email’ and interpersonal communication in the EU, again led by the EU.

How?

The fact that this service is currently designed as a centralised service, apart from being privacy-sensitive, is above all inefficient and somehow absurd: in the age of networks, the fact that in order to write to each other we still have to go through a centralised mediator is simply anachronistic. Certainly, it does not respond to logical reasons, but to domination reasons.

Once again, we ask that an intranational European consortium is established to generate a public code for a peer-to-peer email, that is decentralised and sovereign for each citizen, of course also compatible with the current situation.

3 – The third essential daily digital infrastructure that we refer to in our report is the modern browser.

We are all aware of the existing privacy issues when browsing the internet.

Again, there is no need to reinvent the wheel. A democratic browser already exists since 2004: Firefox. It is already governed based on the purpose economy by a foundation with the goal of preserving digital rights and freedoms.

However, recently, 88% of Firefox’s revenues come from a Search Engine Default Partnership Agreement with Google, making Google its main source of revenue.

It is not difficult to see why it is problematic that Google, in a clearly market dominant position, is the main ‘partner’ in its non-profit Free software competitor.

So: Europe should rescue Firefox. Crazy maybe, but absolutely feasible too. (before some Elon Masks does it or something like that).

4 – The closing part of my presentation and of the report is about sustainability. It mainly addresses the concerning situation we have encountered while wanting to attract talent to develop the public code of DD.

There is a recurring malpractice in public procurement throughout Europe: the systematic violation of national and European regulations on public procurement that, since Directives 23 and 24/2014, require institutions to conduct public tenders in small lots to favor small and medium-sized companies.

Additionally, the absence of clauses for respecting digital rights and ensuring the auditability of products, makes the development of free software companies in particular, extremely difficult.

The data from the European Commission itself shows that a large majority of EU countries do not achieve a level of 50% of public procurements that reach the SMEs. This is due to the lack of lotisation.

In short, the sustainability of sovereign and democratic digitalisation requires antitrust and investment policies that reach SMEs and protect digital rights. That is to say: the simple enforcement of the EU legislation.

Moreover, the institutions are also responsible for allowing the penetration in essential services of big tech products that cost them zero euros, as it is the case in education, health, administration, the email, etc.

It is essentially a violation of the right to conduct a business, because:

-This occurs outside of public procurement, with the excuse that the cost is zero; and

– This “levels” the playing field, preventing competitors from emerging by permiting the beneficiary to grows to the point of becoming “unreachable”.

The fact that citizens use non-auditable software may be because we have no other option or we cannot adapt. However, when an institution continues to use non-auditable and non-interoperable software on a daily basis, it is systematically violating the rights of the population.

In conclusion, for all these reasons, we demand to establish a European coalition to:

1 – Co-create a free, auditable and interoperable European code for public essential services – starting from education, that is accessible to institutions, companies and individuals.

2 – Ensure the correct and prompt enforcement of Directives 23 and 24/2014 so that companies of all size throughout Europe can contribute to this code and benefit from providing derivative services based on it.