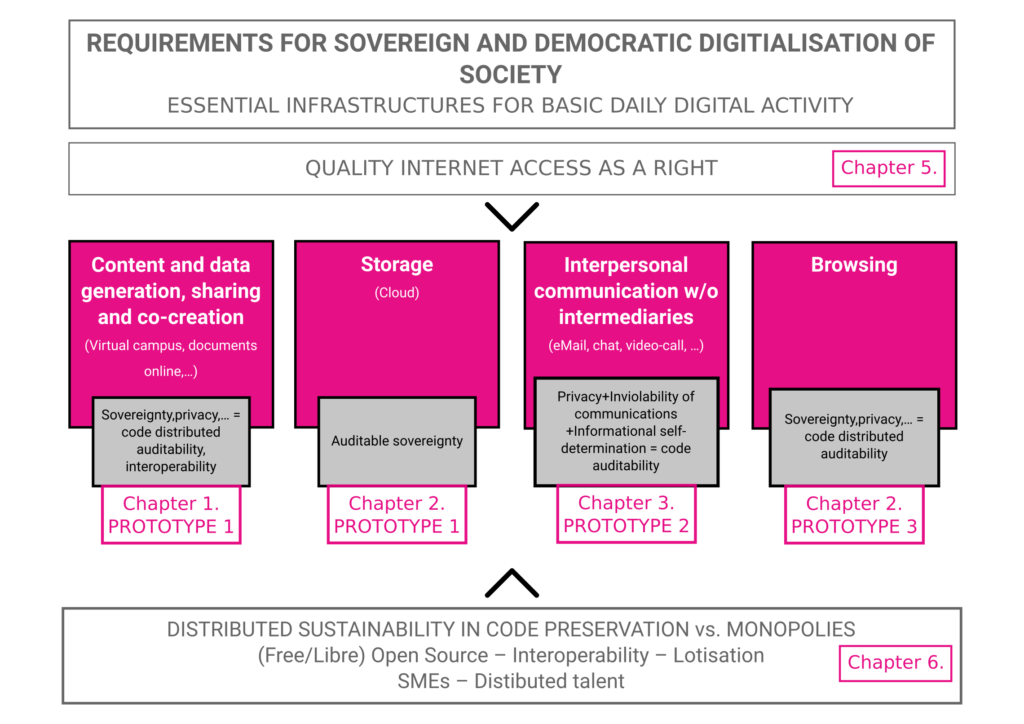

Democratic digitalisation: a digital transition based on human rights and cooperation, by design and by default.

Sovereign digitalisation: digitalisation in which even the smallest actor in the democratic architecture (i.e. the individual citizen) can control, without intermediation, the use and destination of the content and data they generate.

When we talk about digitalisation, we often refer to large infrastructure projects such as 5G or artificial intelligence, or debates about the use of digital in societies.

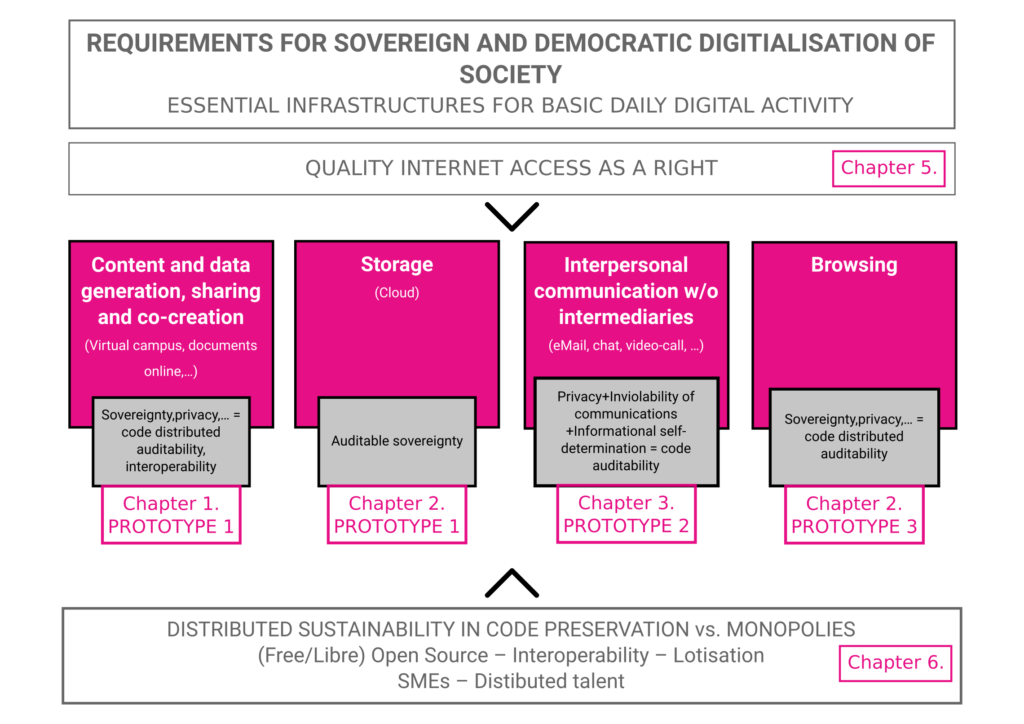

Before all this, however, there is an essential layer that makes everyday digital life possible in all activities of society, from key essential services to individual use: internet access; content creation and storage; online interpersonal communication; browsing, etc.

When this basic layer of everyday digital life systematically violates the rights of the people who use it, everything that is done with it will happen in a framework without democratic guarantees. Operating in clouds where configurations, data and content are generated and stored in a non-sovereign manner is one example of this.

We believe that this is the responsibility of our institutions, which should not be negligent in fulfilling their duties. The success of digitalisation must not be accompanied by the destruction of fundamental rights as collateral damage.

Privacy is the necessary starting point in any system that aims to guarantee rights. Ensuring compliance with democratic principles means being able to audit digital tools and infrastructures to know what they execute; that is to say, we need to make their source code accessible and available to be audited in a distributed, disintermediated way.

Bearing this in mind, only free/libre open-source software tools meet these requirements.

FLOSS has another fundamental advantage: it helps to boost socio-technological entrepreneurship because it is made available to all and, managed rationally, can make public investment enjoy a much longer useful life than proprietary code. Moreover, this perspective of changing consumption patterns at both the individual and, above all, the institutional level is also a way to reduce our ecological footprint.

The fact that the basic everyday digitalisation layer is provided most intensively by only a few Big Tech companies, even in the context of essential institutions and services, is an indication that the wrong signal is being sent to the market: that digitalisation can take place at the sacrifice of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs); at the sacrifice of innovation as a valuable, distributed human capacity; and often at the sacrifice of human rights themselves.

On the contrary, the practical actions/prototypes proposed in our report aim to restructure the economy from the point of view of democratic and sovereign digitalisation, i.e. by making respect for human rights the raw material of distributed business design.

In the report, we address 3 main areas as essential in everyday digitalisation. In all 3 areas we indicate how institutions can rectify the situation.

In addition, two cross-cutting issues are addressed: the digital divide (only the territorial and socio-economic divides are touched upon) and issues related to problems in public procurement.

The situation we have found ourselves in as we tried to harness the talent that exists in the digital domain for code development is a worrying one. There is recurrent malpractice in public tendering.

The systematic violation of national and European regulations on public procurement, which since 2014 obligate institutions to break down tenders into lots in favour of small- and medium-sized enterprises without any clauses for the respect of digital rights, makes the sustainable and quality development of local digital businesses and auditable software companies extremely difficult.

In short, the sustainability of sovereign and democratic digitalisation depends on the enactment of policies against monopolies and in favour of investment to help SMEs. In other words: the simple application of European directives would enable the democratisation of the right to set up a business as part of a more democratic form of digitalisation.

The European Union’s own data show that in many places no more than 30% of public contracts are tendered in lots, while the European average is 50%.

It is a vicious circle: large companies win the bids because the auditable code industry cannot cope with large deployments. The auditable code sector cannot handle large deployments because it is not allowed to improve and grow, as there are no opportunities for it.

While, on the one hand, governments ask citizens to buy locally to revive the economy, they fail to set an example and continue to award tenders to giant and/or multinational companies.

While, on the one hand, governments ask citizens to buy locally to revive the economy, they fail to set an example and continue to award tenders to giant and/or multinational companies.

It is also the responsibility of institutions that Big Tech have been able to penetrate institutions with products offered for “free” in monetary terms, such as is the case in education, healthcare and the post office.

The main risks to competition are related to the fact that:

– This happens outside public procurement, with the excuse that the cost is zero, i.e. outside the market;

– This “levels” the playing field, preventing competitors from emerging; and whoever benefits, grows even further and become “unassailable”.

In short, we call on those administrations that still take digitalisation lightly —and that is the majority of them— to accept and take seriously their responsibilities.

The fact that the public uses non-auditable software may be because we have no other option or because we are unable to adapt to the required change, but when an institution continues to use non-auditable software every day, it is systematically violating the rights of the population; not only their digital rights, but also the inviolability of communications, freedom of enterprise and effective legal protection, among others

While, on the one hand, governments ask citizens to buy locally to revive the economy, they fail to set an example and continue to award tenders to giant and/or multinational companies.

While, on the one hand, governments ask citizens to buy locally to revive the economy, they fail to set an example and continue to award tenders to giant and/or multinational companies.